Speed is a consideration for any website, whether it's for the local barbershop or Wikipedia, with its huge repository of knowledge. It's a feature that shouldn't be ignored. This is why caching is important — a great way to make websites faster is to save parts of them so they don't have to be calculated or downloaded again on the next visit.

My team was recently having a discussion about the parts of facebook.com that are currently uncached, and the question came up: What is the efficiency of the cache since, at Facebook, we release new code twice a day? Are we releasing new code too often to benefit from having resources in the browser cache? In searching for an answer, we found a study on Yahoo's Performance Research blog that looked at the impact of the browser cache on webpage performance.

We were surprised and saddened to see the results: 20% of all page views were coming in with an empty cache. But then again, this study was done more than eight years ago. That was before browsers could show traffic in things like the network waterfall screengrab you see at the top of this post. We're talking just a few months after IE7 and jQuery were first released. Let that sink in for a minute. jQuery 1.0 — yeah, the old-old-old days. With a grain of salt in hand, we decided to run our own numbers and see if things have gotten better since that study was published.

Re-creating the study

In the original study, Yahoo created a new image that was served with a special set of headers. These headers tell the browser that when that same image is requested a second time, instead of doing a normal request do a conditional GET request if the image has changed. This type of GET request passes the Last-Modified header back to the server, and if it hasn't been too long since the image has been modified, the reply can be 304 Not Modified instead of 200 Success. Yahoo then looked at its server logs to do the analysis.

Similar to that, we created a PHP endpoint that could both deliver the image and also log requests to a database.The image was sent with HTTP headers to control the browser cache and any intermediate proxy caches, and we logged all the headers that were sent as part of the request. The headers we sent in our response were:

Cache-Control: no-cache, private, max-age=0 ETag: abcde Expires: Thu, 15 Apr 2014 20:00:00 GMT Pragma: private Last-Modified: $now // RFC1123 format

But for IE7 and IE8, we tweaked two headers to get around some known bugs and instead sent:

Cache-Control: private, max-age=0 Pragma: no-cache

When the browser makes the request for an image, one of two things will be sent along with it to our server:

- No extra headers, because the browser hasn't seen the image before. We reply with a

Status: 200 Successand send the image data so the browser has something to cache. TheLast-Modifieddate andETagvalues are saved by the browser for next time. - One or both of the

if-none-matchorif-modified-sinceheaders, which indicate that the browser has seen the image before. We respond with aStatus: 304 Not Modifiedand no image data. We also set theLast-Modifiedheader in the response to be$header['if-modified-since']instead of$nowso the browser gets the same response each time.

The final decision in the setup was where and when to make the image request. We decided to include an img tag next to the Facebook search bar, which is rendered every time Facebook reloads. During a full-page reload, resources are unloaded from memory, and the browser, depending on the cache headers, will re-request CSS, JavaScript, and our image. So it's the best place to measure if the cache is working or not.

After we had the endpoint ready to log requests and the img tag ready to make those requests, we were ready to start..

Study Results

After a few weeks of collecting data and letting caches fill up, we looked back over the past seven days' worth of data. The initial results were surprising to us: 25.5% of all logged requests were missing the cache. We split the data by interface, desktop and mobile, and still saw the same breakdown: 24.8% of desktop requests and 26.9% of mobile were missing the cached image. Not what we expected, so we dug in more.

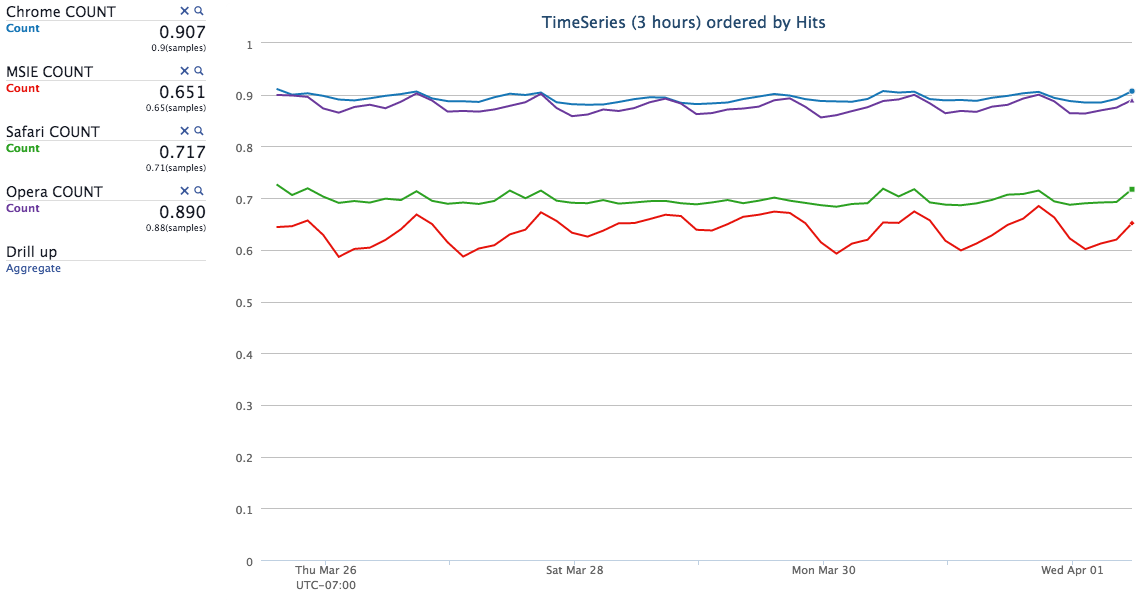

Splitting the desktop numbers by browser made the story much clearer.

Above we can see the hit rate for desktop browsers over the course of a week. People using Chrome and Opera appeared to be benefiting from their browser cache. You may notice that Firefox is absent from the chart, though, and with good reason. Firefox v31 and earlier have an 80% cache hit rate with our method, but the hit rates for v32 and later dropped significantly. The release notes for v32 explain there's a new cache backend, which remembers and reuses recent response headers. If they're reusing responses, then our endpoint won't receive requests and we can't log anything. This would skew our results and make Firefox look like it performs much worse than it actually does. People are still getting local cache hits; we just don't get the information. To account for this, we removed Firefox from our calculations.

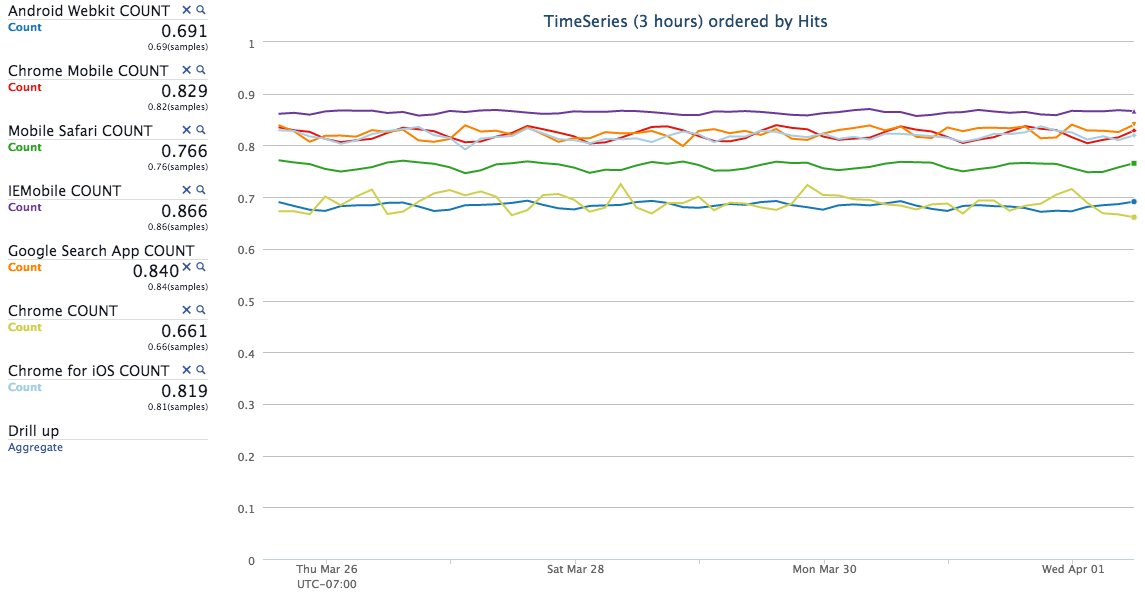

Let's take a look at the mobile story.

There are a few bands up at the 68% and 84% range for cache hits, right in line with what we saw before. There's much more variability in the mobile landscape, though — many different year class devices are hitting the mobile site, and each has a range of possible browser versions. These numbers are a touch lower but otherwise line up with what we saw for desktop.

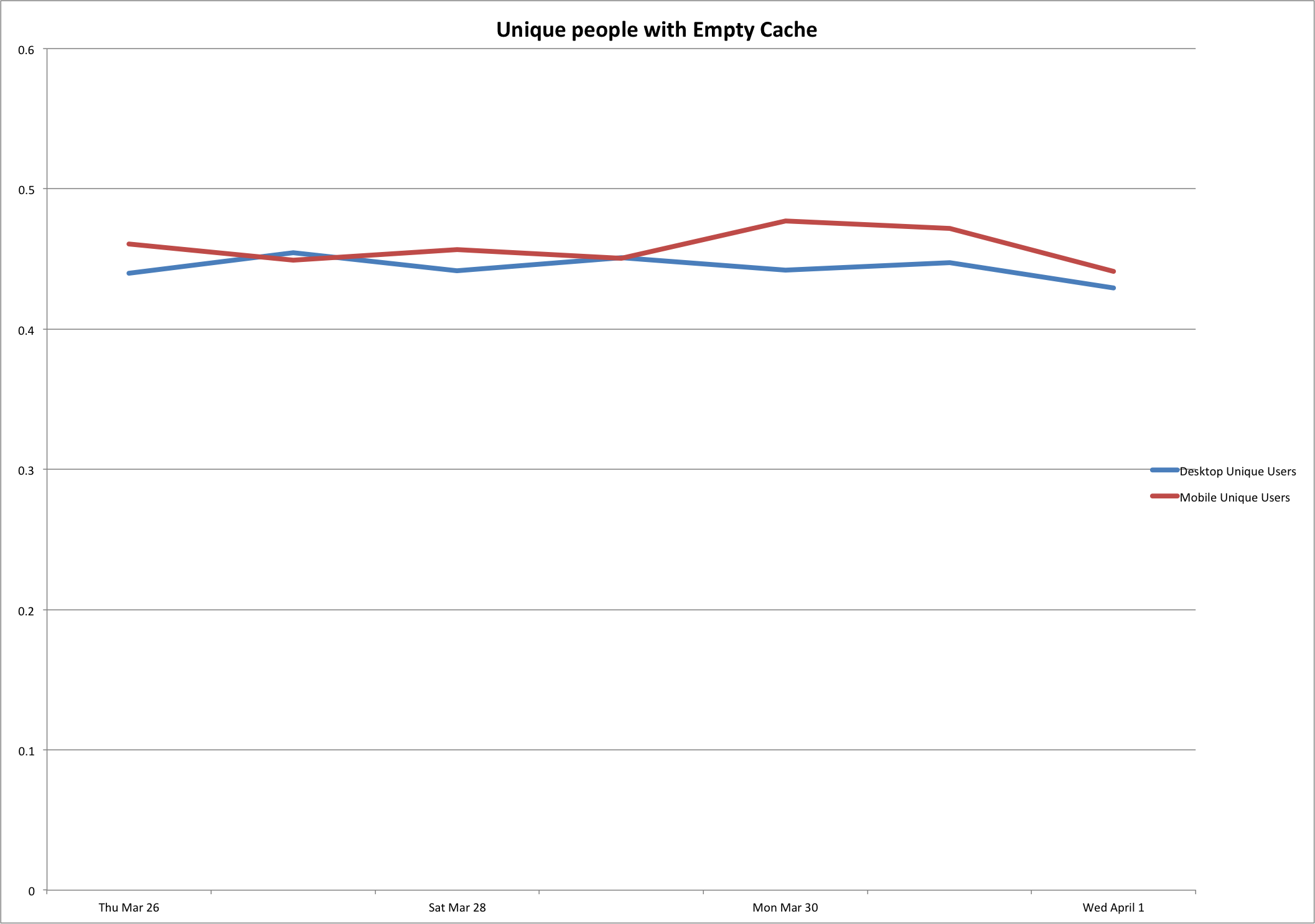

We can also look at what percentage of users are getting an empty cache.

On average, 44.6% of users are getting an empty cache. That's right about where Yahoo was in 2007 with its per-user hit rates.

Taking it further

We're not done yet though. At Facebook, we like to move fast and have twice-daily releases to ship all the great new features that are being developed every day. This led us to ask the question: How long do browser caches stay populated? We can answer that by looking at the if-modified-since request header and subtracting the current time from it. This will give us the length of time that this person's cache has been primed and serving hits.

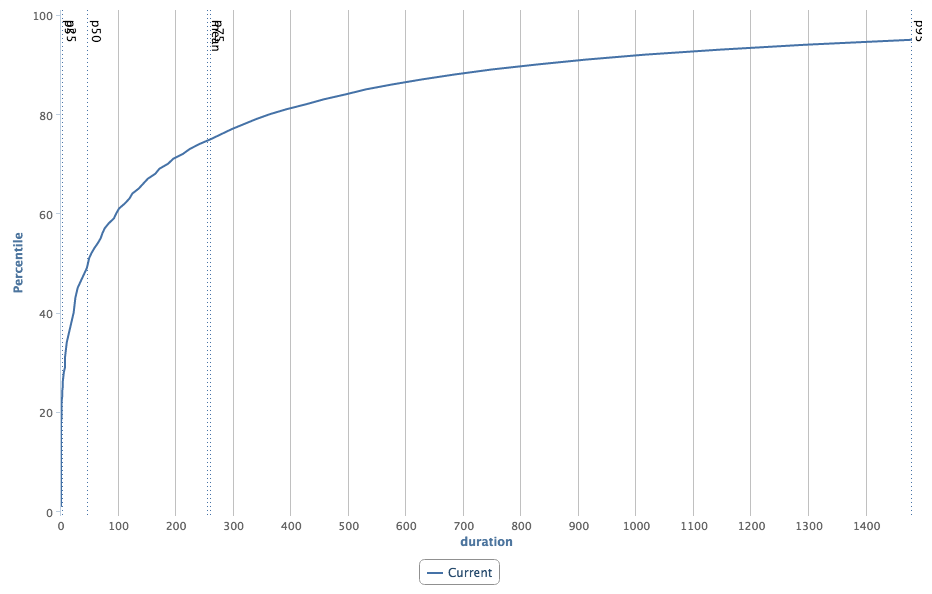

So we dived back into the data. Still looking across the last week of data, we generated a histogram to illustrate the distribution of cache duration values across desktop requests that hit the cache (requests that returned a 304). In other words, how long has it been since that user got the image for the first time?

The duration axis across the bottom is measured in hours, and the vertical p50, mean, and p75 lines indicate how old the cache was for a given percentage of requests. For example, the p50 shows us that 50% of these requests arrived with a cache that was set at most 47 hours ago. Similarly the p75 tells us that 25% of requests have a cache that's at least 260 hours old. Running the same analysis on mobile hits shows there is a 50% chance that a request will have a cache that is at most 12 hours old.

Practical applications

Overall our cache hit rate looks like it has improved since 2007. If we ignore Firefox v32 and newer (where we cannot log some cache hits), then the cache hit rate goes to 84.1%, up from about 80% in 2007. On the other hand, caches don't stay populated for very long. Based on our study, there is a 42% chance that any request will have a cache that is, at most, 47 hours old on the desktop. This is a new dimension, and it might have more impact for some sites than others.

It's easy to understand why caches don't last long in general. Look at how Internet delivery and webpage size have changed between 2007 and today. In 2007, we had 2.5Mbps cable modems (at home), and the Yahoo homepage weighed in at 168.1KB. Today, I get 8Mbps downstream via LTE on my cellphone, and the Yahoo homepage is 768KB. The average webpage is over 1MB today, creating more pressure on our browsers to perform better.

Thus utilizing the browser cache continues to be important and has the potential to give us more impact than it did eight years ago. The best practices tell us to use external styles and scripts, include Cache-Control and ETag headers, compress data on the wire, use URLs to expire cached resources, and separate frequently updated resources from long-lived ones. All of these techniques work together on any website, not just one at Facebook scale. We were worried that our release process might be negatively impacting our cache performance, but it turns out to be not the case. In fact, we are using this data to focus on doing a better job of utilizing the cache for everyone visiting www.facebook.com. Happy cache-hacking.